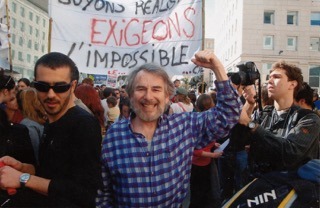

ISE supporter Richard Greeman is a retired professor, was a colleague of Cornelius Castoriadis, Raya Dunayevskaya and Immanuel Wallerstein, and is a prolific translator of the anti-authoritarian Russian revolutionary Victor Serge. Richard is a founder of the Praxis Research and Education Center, based in Moscow, and director of the Victor Serge Foundation. This essay is part of an ongoing study, and is posted here in its entirety to encourage ongoing discussion:

Socialist Internationals in History

by Richard Greeman

This study is based on the premise that any profound social transformation in our era of globalized capitalism would have to take place on a planetary scale. History has shown that revolutionary movements, when geographically isolated, are inevitably either crushed or assimilated into the capitalist world system. This internationalist conclusion first became apparent to working people during the 19th century as capitalism and the Industrial Revolution spread across Europe, and it was first elaborated theoretically by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their 1848 Manifesto of the Communist League with its ringing conclusion: “Workers of the world, unite!”

SIDEBAR

In point of fact, the French socialist and feminist Flora Tristan (1803-1844), ahead of her time, was the first to call for a “universal union” of workers. Moreover, Tristan’s “union” was truly “universal” because she proclaimed the necessity of uniting “workers of both sexes” – in Working Class Unity (L’Union Ouvrière). It took two years before the International Workingmen’s Association, of which Marx was a founder, began to admit women as members and it was three years before a woman, the feminist Harriet Law, was added to the General Council.

The International Revolution of 1848

The very month the Manifesto appeared, revolution broke out in the streets of Paris, with the workers in the lead, and it soon spread all across most of Europe. This was hardly a case of “cause and effect.” In fact, the Communist League, which had commissioned Marx and Engels to write up their principles, was a small group of radical German workers, mainly living abroad, and its Manifesto was mostly read, if at all, after the fact. However, the Manifesto gave systematic expression to ideas that were already in the air. Indeed its authors explicitly avoided putting forth any “special doctrines,” confining themselves to stating the general historical conditions of the workers’ struggle, to proposing autonomous class struggle and international cooperation to win as its method and as its ultimate goal, not just the betterment of labor, but the self-emancipation of labor – a cooperative post-capitalist society called “communism.” This synthesis was indeed prophetic. Before the ink was dry, the struggle for political power between “bourgeois” and “proletarians,” foreseen in the Manifesto, was being played out in the streets of Paris.

The “Year of Revolution,” inaugurated in Paris in February 1848, spread across Europe with the speed of the newly invented telegraph, railroad and daily newspapers connecting France with Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Poland and Italy, sparking revolts in 50 localities (including South America) within months. In Great Britain, the class-based democratic wave took the form of the Chartists, with impressively militant mass demonstrations of workers demanding the vote.

Although the demands of the 1848ers were mainly about democracy (a parliament, male suffrage) and national freedom (from the oppressive Austrian Empire), 1848 was also the first time in history that the working class put forward its own economic demands, took up arms, and marched under its own banner. The famous Red Flag was first unfurled in the streets of Paris alongside the tricolor of the bourgeois Republic in 1848. Unfortunately, the parties of the propertied middle class in France were able to use these workers’ movement as cannon fodder, take power for themselves, and set up a Second Republic. The victorious bourgeois Republicans then turned on their erstwhile proletarian allies, shut down the public works set up for the unemployed, and turned out the National Guard to massacre the workers’ protest demonstrations.

Ironically, having thus cut down their mass base of support, the bourgeois democrats were in turn repressed by the Right. So and after barely two years of existence, the Second French Republic was swept aside and replaced by twenty years of restored monarchy under the authoritarian Second Empire of Napoleon III. Similarly, in the rest of Europe, the once hopeful democratic regimes were put down by the reactionary powers, led by Czarist Russia, ushering in a decade of dark repression.

Although mainly limited to Europe – at that time the only industrially developed region – this “Springtime of Peoples” was the first, and to date most significant example of international revolution in history. These revolutionary regimes, albeit short lived, ultimately succeeded in eliminating serfdom and other forms of feudal oppression, for example in Prussia and the Austrian Empire. The revolutionary wave of 1848 prefigures the international revolutionary waves of 1968 and the rolling revolts of 2011 (from “Arab Spring” to “Occupy”) – although the 1848 revolutions were more powerful and widespread. On the negative side, the 1848 revolutions, like these later waves, although they inspired each other, failed to unite and coordinate in any effective manner. Nor did they leave any international organizations in their wake.

Spontaneous international revolutionary waves have arisen regularly every couple of generations over the last 150 years – 1848, 1905, 1917-19, 1936, 1968, 2011. It is therefore likely, if not inevitable, that they will rise again in the future as globalized capitalism intensifies its attacks on the living conditions of the Billions and on Nature itself. On the other hand it is difficult to see how these waves, although powerful, will be able to wash away world capitalism, which is highly structured, well coordinated, and protected by the state, the police, the army, and a vast propaganda apparatus.

So the second premise of this inquiry is that the next international wave, if it is to wash away capitalism before it’s too late, needs to organize itself. Like the telegraph, newspapers and railroads of 1848, today’s Internet helps to overcome obstacles like geography and, what is more, permits network communication for the exchange of information and the elaboration of goals and tactics on a planetary scale. The subject of this inquiry is the relationship of international revolutionary waves waves and international organization. Waves occur spontaneously and are inspired by sympathy and solidarity, but for solidarity to be effective it needs to be organize– whether by networks, parties, unions, or other structures that will permit mass movements in various regions to establish links, exchange information, organize mutual aid, exploit local victories, and develop strategy and goals.

So our second premise is that our necessary planetary transformation, although based on waves of spontaneous revolt, must be organized. Thus the question we must ask is what kind of organization will best facilitate the goal of a planetary cooperative commonwealth? We will begin by looking at the successes and failures of international organizations during the last century and a half, bearing in mind that organizations can at times be as much a hindrance as a help.

The First, Second, Third and Fourth Worker Internationals

The 1848 Springtime of Nations was swept away by a wave of right-wing reaction culminating in the occupation of Hungary by 300,000 thousand Russian troops under reactionary Czar Nicholas I. Revolutionary internationalism was not to raise its head again until the 1860’s, but by then the workers had assimilated two valuable lessons from the victories and defeats of 1848. First, the danger of class alliances: the workers’ movement must remain autonomous and put forward its own objectives, rather than subordinate itself to the political parties, however democratic, of the middle classes. Second, the need for international organization among working people to coordinate and support each others’ actions.

The First International. In 1862 the rising industrial powers of Europe held a triumphant World’s Fair in London to show off their new products and technical achievements. Workers from France were brought over to London to participate in this orgy of capitalist triumphalism, and some of them took advantage of the free trip to network with English workers as well as London-based German and other European workers. This was the origin of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), better known as the First International. Although it lasted only a decade, at its high point it enrolled up to 8 million members and played an important role in the Paris Commune of 1871, the first workers’ government in history.

The Second International. As the designation “First International” indicates, the IWA was succeeded by at least three other attempts to unite the working people of all lands. The Second, or “Socialist International,” was founded in 1889 and at its high point affiliated more than three million members in socialist parties plus many millions more in cooperatives, trade unions, plus women and youth organizations in more than 20 lands. Its member organizations were pledged to resist the fratricidal slaughter of imperialist war between capitalist states, but in 1914 at the outbreak of the First World War, the Second International collapsed when the Socialist parties of France, Germany, Austria, etc. united with their governments and led their followers into the slaughter-house. The Socialist International’s successors continue today, at least on paper, to unite the Socialist parties of the world, which alternate with the conservatives in power and impose the same capitalist austerity measures (for example under Papandréou’s Greek Socialists and France’s Hollande).

The Third International. A number of anti-war Socialists – among them Luxemburg, Lenin, Trotsky – resisted the Second International’s collapse into “social-patriotism” and held a series of conferences in Switzerland during the war, laying the framework for a new, truly revolutionary and internationalist organization. In 1917 the Russian Revolution put one of these socialist parties in power (the Bolsheviks). At the end of the imperialist World War, a revolutionary wave swept across Europe, and in 1919 the Third (or “Communist”) International was organized in Moscow. However, because of the difficulty for the European anti-war Socialists to get to Moscow, the weakness of their national organizations, and the superior experience and organization of the victorious Bolshevik Party, the Russians naturally dominated the new world organization of labor from the start. From this “natural” supremacy to manipulating the Third International in favor of the evolving national interests of the new Russian regime was but a short step. Slowly, local Communist Parties evolved into rubber stamps, following the twists and turns of the “Party line” dictated by the Politburo in Moscow – up to and including collaboration with the Nazis during the notorious Stalin-Hitler Pact of 1939-1941. The Communist International, or Comintern as it was known, was quietly dissolved during World War II when Russia changed sides again and began collaborating with the capitalist Allies (Britain and U.S.).

The Fourth International. Beginning in the 1920’s, strong resistance developed among revolutionary internationalists within the Russian and other Communist Parties in opposition to this increasingly Russian-centered orientation based on the theory of “socialism in a single country.” Most of this Left Opposition coalesced around the charismatic figure of Leon Trotsky, co-founder of the Soviet state, organizer of the Red Army, and uncompromising internationalist. In 1928, Stalin definitively took over the Party. The Opposition was crushed, Trotsky was stripped of his official positions, expelled from the Party, and driven into exile. There, Trotsky further developed his criticisms, castigating Stalin’s alliance with the reactionary Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai Chek (responsible for mass slaughter of workers), and denouncing Stalin’s insane policy in Germany, where the German Communist Party was made to designate the Socialists as the main enemy (“social fascists”) and to support the Nazi Party in provincial elections under the slogan “after Hitler, us.” In 1938 the exiled Trotsky founded a new, Fourth International in order to win the world’s workers away from Stalin’s vast, powerful Comintern with its network of parties, unions, newspapers, and assassins in every land. In retrospect it was a Quixotic gesture, and the FI splintered into factions within months of its founding and never had more than a few thousand members. However, thanks to Trotsky’s real genius as a political analyst and historian, the influence of the Trotskyist FI was widespread and continues – for better or for worse – to this day.

With this brief summary of the four historical Internationals in mind, I propose to look more closely at each in turn in the hope of understanding their failures, learning from their successes, comparing their organizational forms as a basis for rethinking the vital question: what type of international organization would be appropriate to our age of Internet and multinational corporations?

The Example of the Multi-Tendency IWA

The First International, known at the time as the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), came together in 1864 and fell apart a decade later, not long after the defeat of the Paris Commune. I would like to propose the IWA as a positive model of a horizontal, bottom-up worker self-organization that defined long-term goals and had ramifications among organized workers in many lands. Essentially a correspondence network, the IWA served a practical function by keeping workers informed of each others’ struggles in various countries, and by organizing solidarity where possible. The IWA’s Charter stated that its purpose was to “establish relations between the different associations of workers in such a manner that workers in each country would be constantly informed of the movements of their class in other countries.” In other words, the IWA was first of all an international workers’ information network – today, such a network would be greatly facilitated with the information-sharing technology of the Internet including one-to-many email, interactive sites, social networks, video, and real-time machine translation into various languages.

The basic principles of the IWA were working class autonomy and self-organization. The very first line of the IWA’s Charter states unambiguously: “The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves.” There was no question in the minds of these workers of being led to the promised land by a central committee of professional revolutionaries infused with a correct political line. Indeed, only workers were permitted to be actual voting members of the IWA (although none other than Doctor Karl Marx served as its volunteer General Secretary).

Further, the ultimate goal of the IWA was clear from the start: not just improvement of the workers’ lot but social revolution. The very first sentence of its Charter, quoted above, continues: “The struggle for the emancipation of the working classes means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule.”

It is not that the IWA rejected struggles for reforms like limiting the length of the working day to ten hours. Such partial struggles build confidence and realize tangible practical gains. But they are only means to the ultimate goal of a classless society. Again, the Charter is unambiguous: “the economical emancipation of the working classes is therefore the great end to which every political movement ought to be subordinate as a means.”

Finally, what was original and unique in the First International was precisely its unambiguous focus on class unity across national borders. Again, the Charter: “The emancipation of labor is neither a local nor a national, but a social problem, embracing all countries in which modern society exists, and depending for its solution on the concurrence, practical and theoretical, of the most advanced countries.”

This global perspective is precisely what is sorely needed in this day of globalized capitalism and multinational corporations which pit the workers of one country against those of another. But today’s representatives of the organized working class have failed utterly to meet the challenge. For example when cheap imported Japanese cars began to flood the U.S. market, the United Auto Workers “International Union” (!) joined with the corporations in a “Buy American” campaign rather than reaching out to Japanese auto workers. Today, Detroit is a ghost town, and the only automobiles actually assembled on U.S. soil are Toyotas. Meanwhile in the Eurozone, international capitalist institutions (the European Central Bank, the European Commission, and the IMF) have been waging class war against the working people. Using “salami tactics” they have imposed “austerity” on one country after another: Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Italy and most disastrously on Greece. Faced with these attacks, one would think that the unions and so-called Socialist parties in these countries would reach out to each other, join forces against the common enemy: the pan-European capitalist institutions. But there have been no visible manifestations of international unity or solidarity against a united multinational enemy. Clearly, international class consciousness is in regression when compared to the European workers of 1864. How did this come about? We will turn to that question in a moment.

Now let us look at the organizational structure of the IWA and the role played by Karl Marx, who drafted its Statutes and served as its General Secretary. Let us recall that membership and voting at congresses were at first restricted to “workingmen,” which excluded both women workers (regrettably) and intellectuals (perhaps correctly). It was when the organizers couldn’t find the right words to express their aims in a Preamble that they appealed to “the eminent writer Dr. Marx” to revise the draft, and he eventually accepted the unpaid position of volunteer Secretary and “scientific” advisor (through his addresses to the General Council on history, economics, and politics).

Far from wishing to recruit followers, Marx did his best to remain anonymous in his work as Secretary of the IWA’s General Council. Indeed, at the 186? Conference of the IWA held in ?, almost none of the delegates had ever even heard the name “Karl Marx.” Marx chose this semi-anonymity not only to protect his émigré status in England (in any case very liberal). As he wrote in an 1881 letter to Hyndman, a collaborator in the Second (Socialist) International: “In party programs, it is necessary to do everything to avoid the appearance of direct dependance on this or that author or this or that book.”

Far from being a “Marxist” organization, the IWA was a broad, multi-tendency coalition of worker groups reflecting the theoretical level of the organized workers of its time. In the beginning, the followers of the French socialist Proud’hon were in the majority. The Proud’honists believed in a form of socialism based on mutual credit, and they opposed strikes, revolutions and women’s rights. Also represented were English Owenites (who believed in utopian communities and cooperatives), French followers of Blanqui (who plotted socialist coups d’état), British trade unionists, German socialists, and Italian nationalists. The IWA did not really take off until the economic crisis and strike wave of 1868, and it was “not the International who threw the workers into the strikes, but the strikes that threw the workers into the International.” Only then did Marx’s economic ideas – exposed in his 1865 address to the General Council on the topic “Value, Price and Profit” and in Vol. I of Capital (1867) – win general acceptance.

In 1869, Bakunin and his anarchist followers were accepted into the IWA and introduced yet another political current, federalism, and another political tactic, sectarianism. Bakunin, who was to become Marx’s nemesis in the IWA, was a celebrated revolutionary activist, who had fought on the barricades in 1848, been imprisoned by the Czar for nine years, and had escaped from Siberia returning via Japan, the U.S., London and Switzerland. He was also an active conspirator. As he wrote to his young disciple, the notorious Nihilist Nechayev:

Societies whose aims are near to ours must be forced to merge with our society or, at least, must be subordinated to it without their knowledge, while harmful people must be removed from them. Societies which are inimical or positively harmful must be dissolved, and finally the government must be destroyed. All this cannot be achieved only by propagating the truth; cunning, diplomacy, deceit are necessary.

The reader instantly recognizes the “ends justify the means” doctrine proclaimed by the Jesuits and practiced by the Communist Third International, which eventually degenerated into a network of ruthless Russian agents. The intellectual root of sectarianism of all kinds is the assumption of possessing a monopoly of the truth. From there on, anything is permitted. Nechayev, whom Bakunin defended, was infamous for having organized the murder of a former comrade in order to bind together the members of his conspiratorial cell. This episode was the basis of Dostoyevsky’s 1871 novel The Possessed (also called Demons) which may have done more to discredit anarchism and socialism than any other writing. It is ironic that Bakunin’s faction, which attempted to take over the IWA in 1872, described itself as “anti-authoritarian.” What is more authoritarian than deceit and violence? Nechayev began his revolutionary career by organizing an illegal secret society of radical students in Moscow (?) whose names he then gave to the police so that their arrests would radicalize them.This tactic reminds me of an allegedly Marxist organization of the 1960’s called Youth Against War and Fascism which, in order to radicalize them, led unsuspecting antiwar demonstrators into bloody confrontations with the police. It goes without saying that such elitist theories and tactics are totally opposed to the principles of workers’ autonomy and self-organization unambiguously expressed in the Charter of the First International.

Two years after Bakunin’s entry into the IWA, the Paris Commune, the first workers’ government ever, was established by French workers and soldiers in the wake of Napoleon III’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Although Proud’honists, Blanquists and Internationalists of the IWA participated in the Commune, it was an improvised affair rather than the application of anyone’s theory. In May 1871, after flourishing for three months, the Commune was brutally repressed by the Third French Republic with the help of the Prussians. The wave of repression on workers’ associations spread to every land, and the First International was effectively destroyed as a practical movement – but only after having “stormed the heavens” with the first practical workers’ government.

After the Commune’s tragic defeat, Marx was assigned by the IWA’s London Committee to sum up the basic lessons learned by the Paris workers, for the benefit of future generations of workers. They were “anarchist” lessons: smash the state and replace it with the armed people governing themselves through elected, revocable representatives paid at workers’ wages. Marx was the first to acknowledge that it was not he, the revolutionary intellectual, who created this essential model of workers’ self-government, but the workers themselves through their own experience. Further, Marx made an important change in his major theoretical work, Capital, after observing that the actions of the Parisian workers had “stripped the fetish off commodities” and revealed their exploitative, alienated essence. Marx also radically changed his theory of the state after studying the practice of the self-organized Parisian masses’ three-months of innovative self-defense and self-organization.

If “nothing succeeds like success,” nothing fails like failure. It was later – during the repression following the defeat of 1871 and in the midst of the subsequent quarrels and factionalism among demoralized, embittered, revolutionary exiles – that the famous split took place between Bakunin’s “anti-authoritarian” followers and the so-called “authoritarians” or “Marxists” fighting over the remains of the IWA. Bakunin and Marx had been friends and allies in Paris in 1845, but later quarreled and hated each other. Nonetheless, Bakunin, who appreciated Marx’s intellectual contributions, actually translated Marx’s Capital (1867) into Russian and once wrote “I am your disciple and proud to be one.”

In this ugly aftermath of defeat, the anti-authoritarian conspirator Bakunin attempted to take over the moribund IWA at its 1872 Congress, but he was outmaneuvered by the wily Marx, who then sent the General Council far across the Atlantic to New York. Bakunin contested the Congress’ vote and set up his own, anarcho-syndicalist IWA which had great, and for the most part positive, influence in Spain and survives to this day in a number of countries – albeit divided into tiny warring sects. In retrospect this “battle of titans” seems like a battle of pygmies, revealing the small side of these two bearded, 19th century patriarchs, both blinded by national prejudices (Bakunin’s anti-Semitism, Marx’s paranoid fear of Russia).

Aside from the personality conflict between Bakunin and Marx, the split in the First International brought to the forefront two different approaches to the essential question of the role of the nation-state. In my opinion, these differences were more apparent than real. Both Marx and Bakunin proclaimed the Paris Commune as a model of self-organized working people taking power, governing, and defending themselves. No anarchist could disagree with Marx’s post-Commune conclusion that the workers cannot “take over” the existing bourgeois state with its oppressive apparatus. On the contrary, they must “smash” it and replace it by a form of participatory democracy where elected delegates have limited mandates, are subject to recall, and paid at workers’ wages. A democracy defended not by a state army or police force but by the people in arms under elected officers. After 1871 Marx abandoned his earlier formulation of the workers “taking over” the state for what might be accurately described as an “anarcho-syndicalist” position.

It was Engels, not Marx, who later applied the unfortunate phrase “dictatorship of the proletariat” to the Paris Commune, a formulation which Marx in his lifetime had explicitly asked Engels to abandon, not without reason. Bakunin had correctly written: “They [the Marxists] maintain that only a dictatorship – their dictatorship, of course – can create the will of the people, while our answer to this is: No dictatorship can have any other aim but that of self-perpetuation, and it can beget only slavery in the people tolerating it; freedom can be created only by freedom, that is, by a universal rebellion on the part of the people and free organization of the toiling masses from the bottom up.”

Again, where “Marxists” (not Marx) have argued that although Bakunin’s “free organization of the toiling masses” is the ultimate goal, a temporary, transitional state is necessary to repress the class enemy until such time as a classless society emerges and this transitional state “withers away.” An argument to which Bakunin replied, prophetically, “anarchism or freedom is the aim, while the state and dictatorship is the means, and so, [for Marxists] in order to free the masses, they have first to be enslaved.” The experience of “Communist” Russia, China, Romania, North Korea, etc. confirms Bakunin’s premonition. The problem, as we shall see when we look at the Second, Third, and Fourth Internationals, is that the “Marxism” of the post-Marx Marxists was a total distortion of the basic ideas of the living Marx. The “Marxism” of the Communists had as little to do with Marx as the Spanish Inquisition had to do with Jesus. Indeed, Marx himself famously denied he was a “Marxist”!

Another important issue which divided Marx and Bakunin was the nature of the “subject” of revolution. Marx had deduced from the centrality of industrial capitalism in the world economy that the proletariat or industrial working class – as the producers of wealth and the dialectical opposite of capital – was the central revolutionary class. Bakunin, on the other hand, saw revolution arising spontaneously out of the broad masses, including the peasantry, the artisans and the so-called lümpenproletariat of unemployed or displaced petty-bourgeois and intellectuals, whom Marxists have considered “backward.” Once again, Bakunin was more far-seeing. The great Communist revolutions of the 20th century, the Russian (1917) and Chinese (1949) were based on the revolutionary peasantry, which far outnumbered the proletariat in both cases. Moreover, in the 21st century, we still find “backward” groups like the indigenous, the landless peasants, and the unemployed youth in the forefront of planetary resistance to globalized and financialized capital. On the other hand, Marx was not mistaken to point to the central role of the working class (today largely feminine) in capitalist production: the only class capable of bringing the multi-national corporations to their knees simply by withholding their labor. Thus to understand today’s world, we need to put aside sterile, outdated sectarian squabbles and synthesize the insights of both Marx and Bakunin. In any conceivable future revolution, the decisive blow in overthrowing capitalism from within the belly of the beast will be struck by the workers, but only in alliance with powerful movements among the broader masses of peasants, youth, environmental activists who are today in the forefront of challenging capital’s hegemony.

In any case, as Bakunin himself freely admitted, there is no going around Marx’s economic analysis of capitalism, and today’s libertarian and humanist Marxists have unambiguously repudiated the doctrine of the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” thus opening the way towards greater cooperation and fruitful dialogue between anarchists and Marxists as exemplified by eclectic publishers like PM Press and the Praxis Center in Moscow. Since 1997, Praxis, along with the Memorial Society, has held annual historical/practical international conferences exploring the painful conflicts between anarchists, syndicalists, social-revolutionaries, Mensheviks and Bolsheviks in the tragedy of the Russian Revolution. These discussions, sometimes quite heated, have played the role of a “Truth and Reconciliation Commission.”

Unfortunately, the effects of the 1872 split in the First International still endure, and the two great branches of the socialist family – “anarchists” and “Marxists” – remain sharply divided, to the detriment of class unity. This division is sometimes called the “Red” and “Black” divide, Red referring to the Marxists and Black referring to the anarchists. Germany’s “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck remarked, upon hearing of the split of the First International, “Crowned heads, wealth and privilege may well tremble should ever again the Black and Red unite!” I, for one, sincerely hope that they do unite. For the libertarian moral fervor of anarchism is a necessary additive to the intellectual rigor of Marxism.

Sadly, all that people remember today about the First International is the nasty sectarian split between two factions of what was by then a half-dead exile group, rather than the vigorous and suggestive history of this first and highly successful attempt of working people to organize themselves internationally on their own. But the living history of the IWA, rather than its ugly postmortem, remains rich in lessons for workers today who wish to unite in an international network.

The first lesson is that such an international network must, from the beginning, offer practical advantages by providing facilities for the exchange of information about workers’ struggles, the gathering of statistics about conditions of labor, and the linking of organized workers for international action. With the Internet, this becomes a more practical possibility. Sites like www.labourstart.org, with pages in two dozen languages, are already a mine of information about international labor struggles, while its affiliate, ActNOW, provides support for rank and file struggles.

The next step toward a practical international organization might be the creation of a site mapping class struggles, social struggles and environmental struggles around the world. Such a site would enable solidarity actions across regions, across borders, and across movements, for example coalitions of workers and ecological activists in various lands striking and boycotting one or more multinational corporations. Thanks to encryption techniques like TOR, anonymous worker-correspondents around the world would be able to post real-time reports of their ongoing struggles. Tweet-length bulletins written in uncomplicated phrases could be instantly machine-translated into other languages. Not only does 21st century Internet technology overcome obstacles of geography and language, it also helps overcome the obstacles posed by institutions, whether these take the form of outright state censorship or the more subtle form of corrupted bureaucratic organizations and unions tied to the existing national order.

The second lesson is that collective experience and self-activity, not doctrines, lead working people to their revolutionary discoveries. As Marx put it, self-activity is the workers’ “method of cognition” which the revolutionary intellectual can only later formulate, not prescribe. In other words, there is a movement from practice to theory which precedes the movement from theory to practice. Marx caught the spirit of what he called “the real movement” in both 1848 and 1871 and theorized it. So did Rosa Luxemburg during the spontaneous general strikes that swept across the Russian Empire in 1905. On the other hand the orthodox “Marxist” Karl Kautsky, the main theoretician of the Socialist Second International, could only see the movement from theory to practice, and it was he who taught Lenin the erroneous idea that socialism is “imported into the working class” by party intellectuals.

This elitist notion is in direct contradiction with The Communist Manifesto which unambiguously proclaims: “The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties. They have no interest separate and apart from those of the proletarian as a whole. They do not set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which they shape and mould the proletarian movement […] The theoretical conclusions of the Communists are in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that would-be universal reformer.” (So much for the fetish of “Marxism!”) Both The Communist Manifesto of 1848 and the 1864 Charter of the First International make it clear that revolutionary internationalists distinguish themselves from other participants in the movement in two, and only two, ways: 1) in every local struggle, we look out for the interests of the working class as a whole, worldwide; and 2) in every partial struggle, we look toward the long run, the ultimate historical goal of total worker self-emancipation.

The third lesson is that genuine international workers’ organizations, if they are to leave room for the development of class consciousness through lessons drawn from experience, must avoid sectarianism. They will be, like the IWA, horizontal rather than vertical, multi-tendency and democratic rather than monolithic and authoritarian. What then is our role as revolutionary internationalists in the struggle? Certainly not that of generals or chiefs, but perhaps the more modest roles of leaven; of yeast helping dough to rise; of idea-viruses spreading the contagion of revolutionary thought; of memory-banks and teachers in the movement, making the lessons of the past actual in the present. The role of the intellectual as a “teacher in the movement,” is exemplified in the life and writings of U.S. historian-activist Staughton Lynd.In the words of Maximilien Rubel, “The principle of self-emancipation, placed at the top of the Preamble to the IWA Statutes, forbids the intellectual who wants to struggle in the ranks of the working class to engage in any other activity than political education in the most universal sense of the term: understanding the existing society and aspiration to complete emancipation.”