From our colleague Vincent Gerber in Geneva:

The French « Rencontres internationales d’écologie sociale » recently discussed ways to overcome capitalism. At the center of the discussions: libertarian municipalism as an alternative to the nation-state and the need to renew militancy.

By Les Incontrôlées

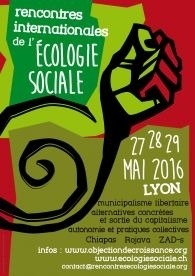

On May 27-29, 2016, radical ecologists, supporters of degrowth, and anarchists gathered in Lyons for the first Rencontres internationales d’écologie sociale (International Social Ecology Gathering). Organized by an international board, it brought together nearly 120 activists, mostly from France, Belgium, Spain, and Switzerland but also from the United States, Guatemala, and Quebec. The official aim was to propose and discuss alternatives to the existing economic and social order. The participants reflected a will to rethink the Left in terms of a radical and resolutely anticapitalist ecology, at a time when the leftist end of the political spectrum has been devastated and deserted and when conservative and far-right thinking is on the rise. In a country marked today by a social turmoil, as labor unions strike against the Loi travail (Work Law) and as the Nuit Debout movement protests a range of issues, these theses couldn’t be more current and accurate.

On May 27-29, 2016, radical ecologists, supporters of degrowth, and anarchists gathered in Lyons for the first Rencontres internationales d’écologie sociale (International Social Ecology Gathering). Organized by an international board, it brought together nearly 120 activists, mostly from France, Belgium, Spain, and Switzerland but also from the United States, Guatemala, and Quebec. The official aim was to propose and discuss alternatives to the existing economic and social order. The participants reflected a will to rethink the Left in terms of a radical and resolutely anticapitalist ecology, at a time when the leftist end of the political spectrum has been devastated and deserted and when conservative and far-right thinking is on the rise. In a country marked today by a social turmoil, as labor unions strike against the Loi travail (Work Law) and as the Nuit Debout movement protests a range of issues, these theses couldn’t be more current and accurate.

The alternatives proposed were inspired by libertarian municipalism, a theory developed some years ago by the American political ecologist Murray Bookchin (1921-2006). His last companion and now biographer Janet Biehl spoke about the implementation of those political principles in Rojava, in northern Syria. This mostly Kurdish region has declared political autonomy amid the civil war in Syria. During the gathering’s first evening this theme was developed by two Kurdish militants, after a showing of the documentary Kurdistan: La Guerre des filles (The girls’ war), in presence of its director, Mylène Sauvoy. The film showed the struggles and the political project of the women’s movement in Kurdistan.

The conflicts in Middle East have made evident the failure of the nation-state, showing it to be incapable of integrating cultural, ethnic and religious minorities as well as women. In Rojava, a radical critique of nation-state has brought about a real autonomy of the base units of democracy. The Kurdish freedom movement has abandoned the aim of creating a homogeneous Kurdish nation-state in favor of establishing a federal system that includes all the ethnic and religious minorities of the area—a prodigious political and social achievement. Lacking innovative political and social ideas, the West will soon fall behind an East that is in the process of reinventing itself, a young Kurdish militant from Paris warned us.

In the new political system inspired by libertarian municipalism and known to the Kurds as democratic confederalism, minorities are systematically represented at all institutional levels. The system is as decentralized as possible: Biehl, who went twice to Rojava, explained that decisions are made first in communes at the level of the residential street and then in councils at the neighborhood, district, and canton levels, with each level sending a delegate to the next one up, charged with relaying the positions taken by the base. It aspires to be a direct democracy, with power flowing from the bottom up, not from the top down, reactualizing the ideals of the Parisian sections of 1793 and of the Paris Commune of 1871. Such a political system is also being attempted in several communes in France, Italy, and elsewhere, so tired are citizens of false political debates and the technocratic administration of the State.

Get inspired by Rojava

During the discussions, everyone agreed that the Rojava system couldn’t be implemented in Europe in the same way, because the context differs greatly. Here too a war is under way, although it remains latent. It’s an ecological and social war that doesn’t bear that name and is attenuated by the existing political system’s numerous safeguards. Social tensions here tend to be easily co-opted or pacified or overwhelmed by the system and by the mass media. Mobilizing its victims will require using other strategies.

Nevertheless, the municipalist and confederal political system that is being constructed in Rojava can be a pertinent alternative in Europe. As a counterpower in the form of a dual political structure, it can take root on the margins of official institutions and develop without trying to initiate an armed revolution. In Turkey as in Syria, Kurdish people didn’t wait to change the constitution before empowering their communes. They put it into practice, and they transformed mayors and their assistants in simple spokespersons for the community.

Libertarian municipalism took center stage at the Lyons meeting because today the Left – and all citizens who fight for greater social equality and more ecological, humanistic and libertarian values in society – must do more than protest. We must create the system that we desire here and now. Political change must accompany social and economic change – and even lead it.

To create our desire

The participants shared a felt need to renew militancy by federating diverse forms of resistance. At this moment movements of workers (labor union struggles) should converge with social movements (neighborhood struggles, site occupations, alternative lifestyles). The links that once united them have been lost as places of residence no longer coincide with the workplaces, isolating people and neighborhoods, making them more vulnerable to an ever more centralized power. It is crucial today to federate our struggles, to explain how they can build on and with one another. To this end we must mobilize ourselves, to share our critiques and our expectations, to recover what we have in common and combine our forces.

The participants shared a felt need to renew militancy by federating diverse forms of resistance. At this moment movements of workers (labor union struggles) should converge with social movements (neighborhood struggles, site occupations, alternative lifestyles). The links that once united them have been lost as places of residence no longer coincide with the workplaces, isolating people and neighborhoods, making them more vulnerable to an ever more centralized power. It is crucial today to federate our struggles, to explain how they can build on and with one another. To this end we must mobilize ourselves, to share our critiques and our expectations, to recover what we have in common and combine our forces.

But renewing militancy means renewing not only its project but its form. Many participants shared experiences that pointed to the urgent need to go to the people first, to start from them and their needs. A broad and lasting political movement can emerge only from local demands, ones that bring people together around a project that speaks for them, that has touched them in the first place – its spectrum can be enlarged afterward. Rebuilding local groups for struggle means recreating agoras and places of formation that express something besides neoliberal discourse and consumerism. We know from Castoriadis and others that change can be effective only when our own thinking is freed from the lies and the illusions of happiness imposed by the market economy. If humanity is to reassert control over its own destiny, the hypnotic hold of economic myths must be loosened.

Many initiators of alternative experiences insisted that their main role is to speak with people, to explain their ideas and proposals, to present them other possible political and economical systems. The aim of the alternatives, be they food cooperatives, reinvented lifestyles, or self-governing politics, is certainly not to oppose frontally the existing dominating system. The system knows very well how to adapt, how to co-opt experiences that annoy or contradict it and how to create conditions to destroy them. The true aim is to create a counterculture that models that what is proposed to us today is not inevitable but is changeable. What can we do with a system that threatens to ruin us yet to which we contribute anyway, despite ourselves? Capitalism is the end of history only if we believe it to be. To sow doubt, to show that another world is possible – and profitable – means breaking the illusions to which masses of right-thinking people submit, even if today’s world repels them deep inside, and starting to alter the balance of forces.

The workshop on “concrete alternatives” contributed to the discussion by reminding us that capitalism was born in tandem with the modern State and that they grew in perfect synergy, defending each other in order to entrench themselves. In the end, capitalism cannot exist without the State, nor the State without capitalism, and both entities should be confronted together.

The origins of capitalism in the sixteenth century were mentioned during the discussion of the commons. The expropriation of the commons – which started with the enclosure phenomenon – coincided with a war against women, whose resistance was a key component of the resistance of farming communities. That war culminated in witch-hunting. Expropriations and the subjection of women were characteristic of the beginning of primitive accumulation of capital, which continues today in new territories. The specific discrimination of women was invoked many times in Lyons, as was the need for gender parity within the movement itself. This led to heated debates, as some argued that feminism has to be integrated into every viable alternative, while others insisted that categorizing a specific discrimination tends to divide a movement.

Reports on the workshops and discussions will be published on the event’s website (www.rencontresecologiesociale.org), on the website Ecologie sociale (www.ecologiesociale.ch), and in a forthcoming book.

The next social ecology meeting will take place in Barcelona in 2017. In the meantime discussions will continue all around us, about how to infuse real democracy where it exists only in name, and how to leave to our progeny something besides a world dominated by a deadly, unjust, and destructive system. The prospects are slight, but offering hope is an important factor in reinventing ourselves and in daring to change.