Published in Anarchist Studies 25:1, pp.103-105.

By Eleanor Finley, University of Massachusetts Amherst, PhD student & ISE Board member,

and Dr. Federico Venturini, Independent Researcher and Activist, Transnational Institute for Social Ecology

A review of Janet Biehl, Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin, Oxford University Press, 2015

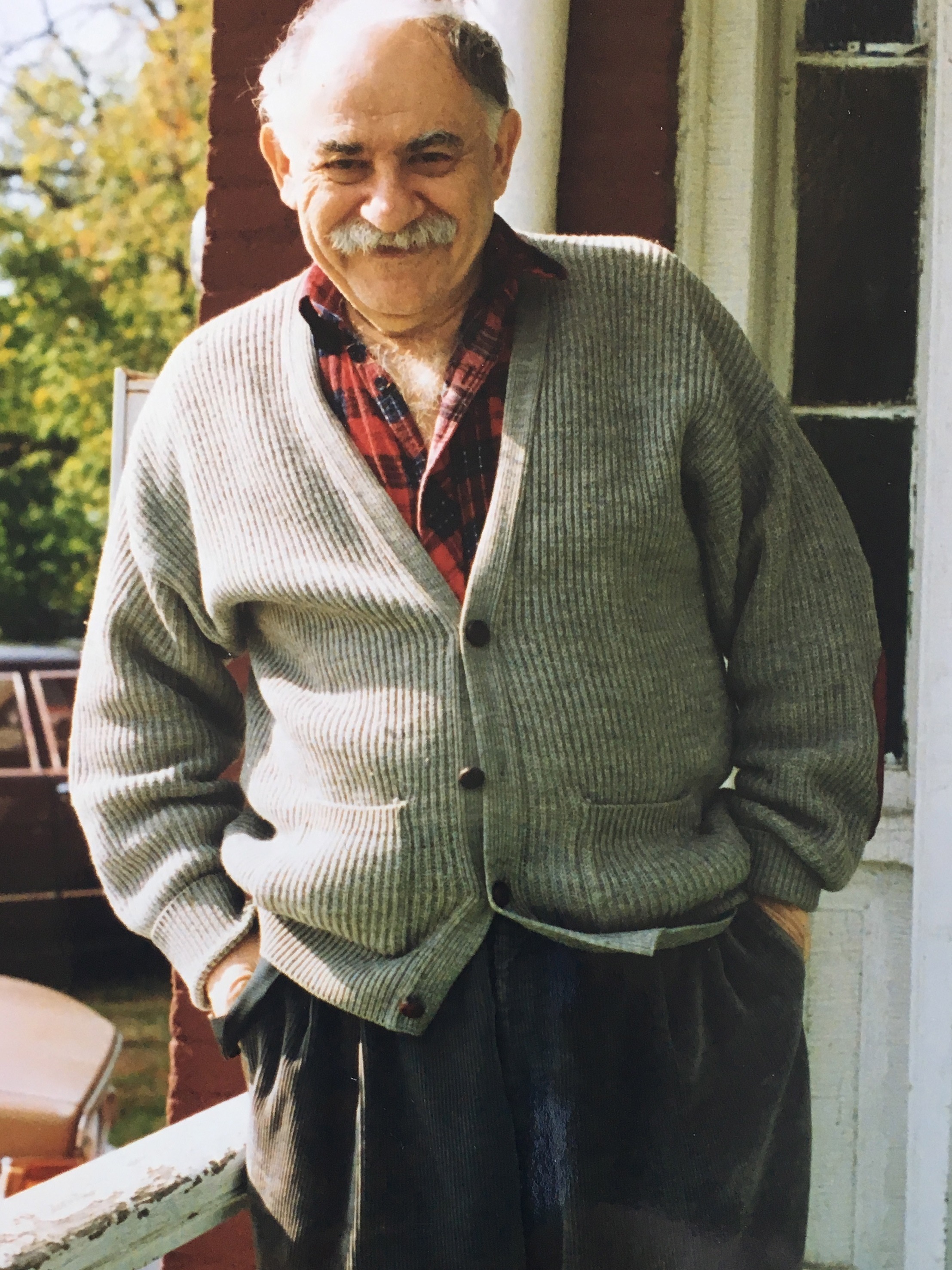

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in the work of leftist political philosopher Murray Bookchin. Given these events, now seems like a perfect time for the release of a biography about this thinker who dedicated his life to bringing about a coherent vision of a truly democratic and ecological society. Such a book might help those interested in radical and coherent social change learn about Bookchin’s personal life, his development as a thinker, and the interplay between his pioneering ideas and the environments in which they flourished. Last year, Janet Biehl released Ecology or Catastrophe: the Life of Murray Bookchin, a biographical sketch of Bookchin, her live-in partner of eighteen years. While Biehl accomplishes some of these goals, upon reading the book we found that it also contains troublesome omissions and misrepresentations of Bookchin’s personal life and political work. As students of Bookchin’s close friends and collaborators we could see that these were frequently errors of omission, and thus difficult for the average reader to detect. Our concern was shared by a number of Bookchin scholars, friends, students, and family, spurring additional research and our critical re-examination of the biography.

In Ecology or Catastrophe Biehl narrates Bookchin’s personal and political development in thirteen chronological and thematic chapters. Setting the stage through extensive research about 1930s-1950s-era politics and leftism, Biehl follows his upbringing in the depression-era Bronx through the New Left, the Anti-Nuclear Movement, the Green Movement, and his critical engagement with most of the major movements on the Left. For the first sixty-five years of this story, Biehl must rely on others for information. Yet rather than drawing on her interviews and accounts from those close to Bookchin at the time, Biehl relies heavily on personal recollection of Bookchin’s beliefs and motivations. This approach erases from the narrative key figures behind some of Bookchin’s major activist projects.

A first example of this kind of omission regards the Anarchos group (1966- 1971), the publishing collective and affinity group based in New York City led by Bookchin and his then-wife Bea Bookchin. It was during this period, surrounded by the revolutionary spirit of the New Left, urban uprisings, and 1960s radical cultural experiments, that Bookchin published some of his most salient work about ecology, post-scarcity anarchism, Marxism, and alternative forms of political organisation. Within the electric atmosphere of the late-1960s Lower East Side, the Anarchos group played an important historical role by articulating the powerful affinity between ecological and anarchist thought.. Yet despite the importance of this political group, virtually nothing is said in Biehl’s book about its members, contributions, and position.

The omission of the Anarchos group and other events ties closely to the conspicuous absence of Bea Bookchin, who was personally and politically close to Murray Bookchin for six decades. Murray Bookchin was married to Bea Bookchin from 1952 until 1963, yet continued to live with her as a close friend, confidant, and housemate for a total of thirty-five years. While any biographer must make decisions about what things to leave out, it is difficult to view Biehl’s account of Bookchin’s life as credible when such a key individual is entirely absent from the book. For instance, Bea was a central figure in the Burlington Greens during the group’s entire duration from 1981-1991. She ran twice for city council as a Green candidate, and spearheaded the Green opposition to a Burlington waterfront development. Despite this, Biehl’s sole mention of Bea in this period is a passing reference to the words ‘Bea for Burlington’ in a campaign poster she claims Bookchin disliked (p262).

Similar problems are extant in regard to most of Bookchin’s close comrades and intellectual collaborators, especially women. Biehl’s erasure of virtually all of the other women who participated in Bookchin’s political milieu paints Biehl as the sole female protagonist in Bookchin’s life, and, whether intentionally or not, is a distortion of those women’s sensibility and intellectual reach. Lastly, Biehl’s biography becomes problematic in her portrayal of Bookchin himself. In the book’s final chapter, which takes place during the last five years of his life, a wealth of odd and inappropriate personal anecdotes takes over the narrative. She seems to oscillate from adoration and awe of Bookchin, to degradation and belittlement. Contrary to Biehl’s depiction, Bookchin was not the despondent and confused man present at various junctures in this book. As a philosophical idealist, Bookchin often chided those around him out of depressive thoughts, declaring political cynicism and despair as an admission of defeat to an irrational society.

We appreciate that the depiction of a powerful, complex and dynamic thinker is a challenging endeavour – particularly for an author so intimately related to her subject. We can understand, even though Biehl eventually departed from his political philosophy (p306), why she might want to share her intimate knowledge about Bookchin’s life, and offer him some of the long overdue credit he deserves. Yet, by diminishing people crucial to Bookchin’s life, Biehl has deprived her readers of an accurate understanding of Bookchin’s political background, sensibility, and influences. No biography is ever complete or objective, yet a full and accurate account of this fascinating, complex, and important figure remains to be told.