Learning from History, Going on From Here

(originally published on Grace’s blog, Organic Revolutionary)

The world has changed considerably in the forty years since I attended my first NOFA (Northeast Organic Farming Association) Conference–then also billed as a “celebration of rural life.” So too has the organization, which has gone from a marginal little group of idealists and back-to-the-landers to a credible, even venerable institution that has influenced and educated several generations of ardent organic advocates—including this one.

Although I had proposed a workshop on “Climate/Food Justice,” I was asked to do a talk about our history, in keeping with the conference theme of “Honoring Our Roots, Tending Our Future.” The most recent issue of NOFA’s esteemed  quarterly publication, The Natural Farmer, featured a thoughtful and well-crafted NOFA history piece by Editor Jack Kittredge with some extensive quotes from Organic Revolutionary. Maybe my long-time NOFA colleagues, many of whom have been vociferous critics of the USDA National Organic Program, have begun to listen to what I have to say.

quarterly publication, The Natural Farmer, featured a thoughtful and well-crafted NOFA history piece by Editor Jack Kittredge with some extensive quotes from Organic Revolutionary. Maybe my long-time NOFA colleagues, many of whom have been vociferous critics of the USDA National Organic Program, have begun to listen to what I have to say.

I made the three-hour trek to Hampshire College in Amherst, MA on August 10th with a mixture of anticipation and dread.

Anticipation

I was looking forward to seeing old friends, though I knew that the “old guard” is no longer much in evidence at these conferences. I was saddened by the recent death of Bill Duesing, who was a fixture of the organization since before he pulled together the CT-NOFA chapter. Katherine DiMatteo, former executive director of the Organic Trade Association (OTA), hosted me overnight, and it was a joy to catch up with her activities for the Sustainable Food Trade Association.

This conference is always a wonderful opportunity to learn something new and different. I was able to attend only one workshop other than the one I was presenting, and chose to listen to Bill MacKentley, founder of St. Lawrence Nurseries on the subject of the fourth phase of water. Bill’s fascinating and information dense presentation motivated me to learn more about the unique ways in which water is structured, and why this is critical for all living organisms. According to Bill, this understanding might even explain the effectiveness of Biodynamic preparations and Homeopathy. How, I wonder, might it also be used to design biologically activated water-based production systems that can be just as healthful as those based in soil?

Native American seed keeper Rowen White shared her wisdom at Friday evening’s keynote program, and on Saturday Food First’s Eric Holt-Gimenez spoke about his latest book, A Foodie’s Guide to Capitalism. In their own ways, each of them stressed the importance of working together for a common vision of planetary healing and social justice, across differing perspectives and opinions. Diversity of viewpoints, besides being more interesting and challenging, helps us form broader based movements than are possible if we only preach to the choir. Both of course knew that’s what they were doing.

Running into former students is always a special treat too, and I encountered two of them just as I was making my escape on Saturday before the dreaded “debate.” Ben Grosscup was a young student in the Institute for Social Ecology (ISE) Summer Program in the early 2000’s, and has recently served as coordinator for the NOFA Summer Conference. Now his work is devoted to supporting activists with song through the People’s Music Network.

As I was talking with Ben, Johanna Mirenda showed up, and we decided to meet for dinner on our way home. Jo worked as Technical Director for the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) from her home in Vermont while pursuing her MA in Sustainable Food Systems at Green Mountain College, where I taught the on-line course in Theory & Practice of Sustainable Agriculture. I was thrilled to learn that she has now joined OTA as Farm Policy Director, and we talked about working to bridge the age-old chasm between the “grassroots and the suits” through our common involvement in the Vermont Healthy Soils Coalition.

Dread

The feeling of dread I brought with me centered on the NOFA “debate” scheduled for Saturday evening…though why anyone would choose that activity rather than music and fun is beyond me. While the central question it posed of “Where do we go from here?” is an important one, the general lack of contrasting views about the definition of “here” leaves something to be desired—thus my use of quotes around the word “debate.”

Paraphrasing some of the statements made by the four “current thought leader” panelists in this program, the starting assumption was that the USDA Organic label has lost its meaning, has been corrupted by industry influence, and is weak at best or fraudulent at worst. Nobody who might disagree with such assumptions was invited. I have not seen a report on the outcome, or whether there was an audience vote on the three choices given in the program — whether USDA Organic is “fraudulent,” “inadequate,” or “worth supporting.”

Arriving in time for dinner on Friday evening I sat down by myself, curious to see who might come talk to me. The first person to sit down at my table was a young woman who was also wearing a “presenters” badge. Her workshop topic about fungi and soil fertility is a subject dear to my heart. I offered a brief explanation of my presentation on organic history and suggested that I had some concerns about the “debate” scheduled for Saturday.

Our conversation began with her statement, made with some certitude, that the USDA Organic program was totally corrupt and untrustworthy. I pressed her for evidence of this claim and received vague suggestions about the corporate connections of those in charge, referring to the NOSB (National Organic Standards Board). I explained that the NOSB is strictly advisory and not in charge of setting or enforcing standards; career civil service employees who are bound by strict conflict of interest requirements are actually the ones in charge of these activities. I used to be one of them.

She offered another general statement about the terrible corruption of the current administration in Washington (no argument there), referring to Scott Pruitt, disgraced former EPA Chief, as an illustration. I pointed out that even the Secretary of Agriculture was hardly involved in managing the National Organic Program, and that the recent USDA decision to pull a final regulation on animal welfare was not one made by National Organic Program staff—who had worked for years to develop and finalize this rule that the organic community supported. Unconvinced, the woman got up to leave, and I invited her to engage further, handing her a book flyer with my workshop schedule on it. “No thank you,” she said, dropping the paper on the table as she departed.

Meanwhile, another woman who had joined the table was eavesdropping on this conversation and exchanged knowing looks with me as the first woman got up to leave. “I’ll take that,” she said, picking up the rejected flyer and smiling at me. She was among the handful who attended my workshop the next morning and engaged the conversation with well-informed questions. See the section below for a key message from my presentation.

Finding even a few people who “get it” gives me some hope for the world. But I continue to be concerned about the divisiveness of ongoing attacks on the integrity of the organic label from within. It has become commonplace to hear, even from knowledgeable consumers, concerns that the organic label doesn’t have much meaning anymore, and may not be much different than the cheaper conventional corporate fare.

Beyond sowing consumer confusion, such attacks feed the real opposition to “real organic” coming from the likes of Henry Miller, a right-wing commentator in The Wall Street Journal. While it is important to be critical and demand accountability, attacks on the trustworthiness of the whole program provide cover and ammunition to the forces of agribusiness as usual to do things like withdraw regulations that have been vetted and supported by the organic community.

The real threat to organic integrity, as I see it, is the impulse to play fast and loose with the truth in order to win. Personal attacks, the blame game, and propagandistic half truths are rightly discredited when used by politicians. Why, then, are so many organic leaders imitating such tactics? The increasing polarization of public rhetoric, which tends to represent any substantive disagreement as a contest between “good” and “evil,” is the scariest thing about our current socio-political moment. Knowing that the political roots of the organic project are not necessarily so socially progressive, we must be careful to avoid the trap of seeking to “make organic great again.”

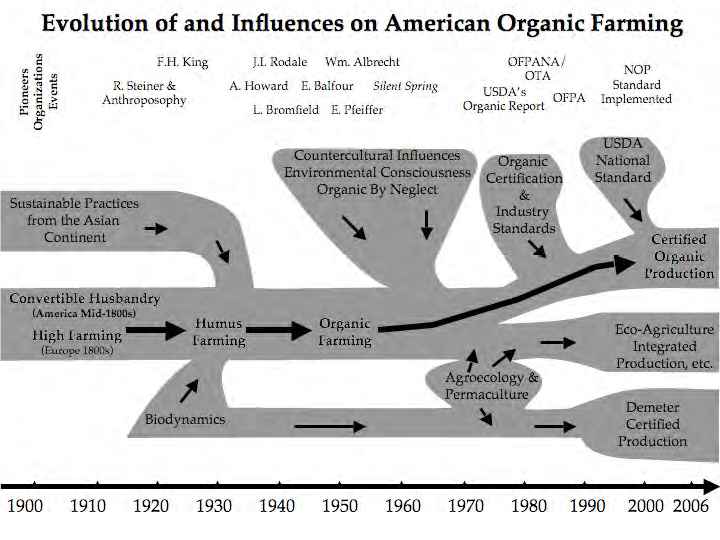

Graphic from A Brief Overview of the History and Philosophy of Organic Agriculture by George Kuepper

A Brief History of Organic

My presentation emphasized the checkered political history of the organic movement, which became a fertile seedbed for the diverse food movements that come out of it. My message was that, while they may differ in emphasis and degrees of holistic vision, as well as having some strong disagreements about political alignment, advocates of each of the variations on the organic concept that have emerged post-1970 are all working towards similar visions of a new paradigm for agriculture and the food system.

One of the little known facts of organic history is its roots in fascist ideology and colonialism. As noted in Chapter 1 of Organic Revolutionary, the connection of the early organic movement to fascist sympathizers is chronicled by Philip Conford in The Origins of the Organic Movement. Here is how I explain it:

Among the more persistent myths of the current organic scene is the notion that the modern organic movement sprang from a strictly left-progressive political philosophy. While partially true, it is a mistake to believe that the political left has any claim to ownership of the organic project, or that organic agriculture (or any green technology, for that matter) is inherently politically correct. Rather, the thinking that shaped the organic vision can be traced to both left-wing and right-wing ideologies, and it is apparently the right wing that informed the first consciously organic advocates in Europe. As laid out in excruciating detail by Conford, many of the founders of the Soil Association, with the exception of a few like Sir Albert Howard, were avowed fascists who supported Hitler and Mussolini before these dictators became enemies of the British state.

Steiner’s followers in Europe, primarily Germany and Austria, were similarly not all repulsed by the Nazi embrace. Anthroposophy, the spiritual credo founded by Steiner and the basis for his agricultural instructions, “had a powerful practical influence on the so-called ‘green wing’ of German fascism,” according to Social Ecologist Peter Staudenmaier. It was largely, he suggests, through biodynamic agriculture that this influence occurred. The well-known Nazi slogan, “Blood and Soil,” was the rallying cry of this green wing, which held that “environmental purity was inseparable from racial purity.”

It should go without saying (but still must be said) that none of this means that practitioners of Biodynamic agriculture or avowed Anthroposophists are really fascists at heart. As acknowledged by Staudenmaier and consistent with my own experience, most of those who today espouse Biodynamics, and certainly those who practice its methods without endorsing its religious aspects, tend to be politically liberal, open-minded, and compassionate folks.

But I cannot help but shudder at the common emphasis on purity amongst some organic true believers. The enthusiasm of some of the right-wing organic crowd in the US for Biodynamics and its array of mysterious cosmic forces can give one pause as well. We would all do well to acknowledge our ambiguous and not always high-minded histories.

The USDA Organic label is now widely recognized as a credible, third party verified marketing claim. It is a big mistake to present valuable concepts such as “agroecology” and “regenerative agriculture” in opposition to “organic”. In saying that “you can’t dismantle capitalism with a marketing plan,” I suggest that we can and must go “beyond” organic to get at the root causes of our interconnected social, environmental, and health crises. But we need not disparage our roots or each other—weakening the power of the organic label to raise public awareness about those problems—in the process.