By Brian Tokar, for The Long View No. 19, Spring 2015, a publication of the Oregon State Bar Sustainable Future Section

The 45th anniversary of the original Earth Day is here, and many elder environmentalists are still nostalgic for the heady days of the 1970s, when 20 million people hit the streets. Although Earth Day 1970 was largely a staged event, it was also the largest outpouring to date of public sentiment on any political issue. It drew attention to environmentalism as a social movement in its own right, perhaps for the first time, and it set the stage for the passage of our most ambitious environmental laws. These laws helped clean up waterways that were turning into sewers, save the bald eagle and other species from the ravages of DDT, and clear the air, which in the early 1960s was so polluted that breathing was hazardous to health in some cities.

The planet has also suffered widespread ecological damage since 1970 and, in the words of renowned climatologist James Hansen, climate change is the “predominant moral issue of this century.” Yet Earth Day is no longer a day of visible protest against corporate exploitation.

As Naomi Klein, British journalist Johann Hari, and others have reported, and as I explained in some detail in my 1997 book, Earth for Sale (South End Press), this is partly the result of increasing collaboration between corporate-styled environmental NGOs and the world’s most polluting corporations. Around climate policy, this collaboration took the form of an alliance, known as USCAP: the US Climate Action Partnership, formed in 2007, with members such as Duke Energy, DuPont, GE and GM, along with corporate-friendly environmental groups. USCAP led the way in pushing for the “market-based” approach to climate legislation known as “cap-and-trade.” Its main result would have been a vast, highly speculative market in carbon credits and offsets, with gigantic payoffs for corporations and precious little benefit for the climate. Cap-and-trade legislation in the US thankfully faltered in early 2010 under pressure from both right wing anti-tax fanatics and market-skeptical environmentalists.

How did such an alliance come about? Throughout the 1970s and eighties, representatives of the largest national environmental groups became an increasingly visible and entrenched part of the Washington political scene. As the appearance of success within the system grew, organizations from the National Wildlife Federation to the Environmental Defense Fund restructured and changed personnel so as to more effectively play the insider game. The environmental movement became a stepping stone in the careers of a generation of Washington lawyers and lobbyists, and official environmentalism came to accept the role long established for many regulatory advocates: that of helping to sustain the smooth functioning of the system. Environmentalism was redefined, in the words of historian Robert Gottlieb, as “a kind of interest group politics tied to the maintenance of the environmental policy system.”

This shift in the character of the most nationally visible environmental groups spelled the end of bold new policy initiatives on behalf of the environment. An environmental mainstream adapted to “insider” politics proved incapable of sustaining even a moderate Congressional consensus in favor of environmental protection, and ultimately helped prepare the stage for the anti-environmental backlash of the 1980s and beyond.

By 1990, most mainstream politicians claimed the mantle of environmentalism. So it was not a huge surprise when the celebrations of the twentieth anniversary of Earth Day in 1990 became the coming-out party for a more overtly corporate outlook. Earth Day celebrations became a virtual extravaganza of corporate hype, and “green consumerism” was the order of the day. The overriding message was simply, “change your lifestyle”: recycle, drive less, stop wasting energy at home, buy better appliances, etc. And while the national Earth Day organization turned down over $4 million in corporate donations that didn’t even meet their rather flexible criteria, celebrations in major U.S. cities were supported by notorious polluters such as Monsanto, Peabody Coal and Georgia Power. Everyone from the nuclear power industry to the Chemical Manufacturer’s Association took out full-page advertisements in newspapers and magazines proclaiming that, for them, “Every day is Earth Day.” The now-familiar greenwashing of Earth Day had begun.

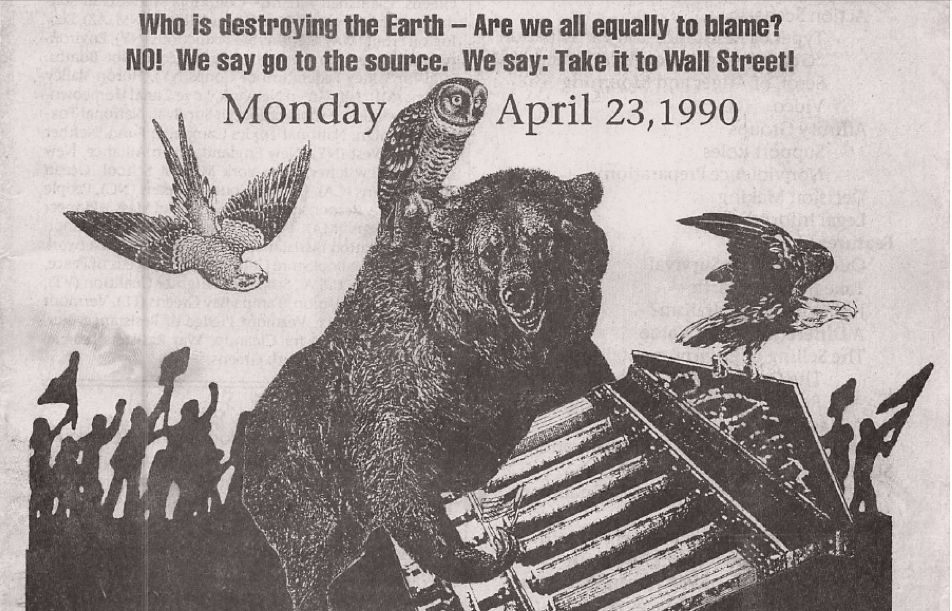

Some activists responded by organizing more politically challenging local Earth Day events of their own, focusing on local environmental struggles, urban issues, the nature of corporate power and a host of other problems that were systematically excluded from most official events. Left Greens and Youth Greens in the Northeast initiated a call to shut down Wall Street the Monday following Earth Day, and were joined by environmental justice activists, EarthFirst’ers, ecofeminists, New York squatters and many others. In the early morning of April 23rd, 1990, just after millions had participated in polite, feel-good Earth Day commemorations all across the country, hundreds converged on the New York Stock Exchange, with the goal of obstructing the opening of trading on that day. Juan Gonzalez, in the following day’s New York Daily News, wrote: “Certainly, those who sought to co-opt Earth Day into a media and marketing extravaganza … almost succeeded. It took angry Americans … to come to Wall Street on a workday and point the blame where it belongs.” [See note below for more on this landmark event.]

The 1990 Earth Day Wall Street Action reflected the flowering of grassroots environmental activity that had emerged throughout the 1980s, partly in response to the compromises of the big environmental groups. The popular response to toxic chemical pollution—launched by the mothers of Love Canal—grew into a nationwide Environmental Justice movement that exposed the disproportionate exposure of communities of color to toxic hazards. Others joined in solidarity with indigenous peoples’ movements around the world that had arisen in defense of traditional lands, responding to the new onslaught of neoliberal development policies. During the lead-up to Earth Day 1990, a hundred environmental justice activists signed a letter to the eight largest national environmental organizations challenging their increasing reliance on corporate funding and tepid support for communities of color.

Today, on Earth Day, the green marketing of products is alive and well, from Priuses to luxury ‘ecotourism.’ Corporations view concerns about climate change and ecological degradation as little more than marketing opportunities. Indeed one Dutch study of consumer behavior suggested that ethical consumer choices are made chiefly for the added social status they confer. “Researchers found consumers are willing to sacrifice luxury and performance,” for example by buying a Prius instead of an SUV, “to benefit from the perceived social status that comes from buying a product with a reduced environmental impact,” The Guardian reported.

Today, right-wing pundits depict environmentalism as an elite hobby that threatens jobs, while many progressive environmentalists cite the potential for “green jobs” to help reignite the economy. Both views are missing a central element of what has made environmentalism such a compelling alternative worldview since the 1970s: the promise that reorienting our society toward a renewed harmony with nature can help spur a revolutionary transformation of society. This outlook has helped inspire antinuclear activists to sit in at power plant sites, forest activists to sustain long-term tree-sits, and environmental justice activists to stand firm in defense of their communities. It is at the center of a new generation of resistance to the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure today. With climate chaos looming on the horizon, such a transformation is no longer optional. Our very survival now depends on our ability to renounce the status-quo and create a more humane and ecological way of life.

Endnote:

The call to the 1990 Earth Day Wall Street Action was drafted by social ecologists affiliated with the Left Green Network and the Youth Greens. In her important book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate (p. 206), Naomi Klein incorrectly attributes it to the National Toxics Campaign and other mainstream groups that signed on as endorsers of the event, but were not among the initiators. Klein’s account appears to be based mainly on a news report from the support action at the Pacific Stock Exchange in San Francisco that same day. A scan of the 64-page Earth Day Wall St. Action Handbook is now available online at http://www.scribd.com/doc/220344101/Earth-Day-Wall-Street-Action-Handbook. Along with our call to action and organizing details, the handbook includes articles by Chaia Heller, Ynestra King, Murray Bookchin, Howard Hawkins, John Mohawk, Brian Tokar, and many others, plus 6 pages of corporate profiles and an extensive bibliography.

Also Paul Messersmith-Glavin, formerly of the Youth Greens, has posted an excellent first-hand account of the 1990 Wall St. Action at http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/04/23/remembering-the-earth-day-wall-street-action.